The Mysterious Matsumoto Hoji: the ubiquitous woodblock artist that no-one knows anything about.

·

8 May 2023

·

2 min read

If you’ve spent any time browsing Japanese artwork on the internet, you will have no doubt seen Matsumoto Hoji’s notorious frog prints. Their minimalist composition, classic ukiyo-e style and the inimitable charm of their amphibian subjects make them a wildly popular addition to several peoples’ art collections. Google his name and you’ll see thousands of reproductions of his famous frogs - but trying to find any background information on the man himself is almost impossible.

The print itself is typical of Japanese artwork at the time. It embodies the principles of wabi-sabi, a philsophy that values simplicity, imperfection, and impermanence, and draws on the folkloric symbolism of the frog in Japan. In Japanese mythology, the frog is a symbol of good luck and prosperity. The legend of the "lucky frog" states that if you catch a frog and release it back into the wild, it will bring you good fortune.

So what do we know about Hoji? In order to find out, we have to take a look at where his infamous frog prints were taken from: the “Meika Gafu”.

A popular mass-produced publication from the later Edo period, the Meika Gafu (名家画譜) was first printed in 1814 by Eirakuya Tōshirō, a prolific publishing house in Nagoya, Japan. Tōshirō was founded towards the end of the 18th century by Katano Naosato, a member of the “goyo shonin” class, whose job it was to serve the Shogun of the area with whatever goods were required by the area. He started by publishing collections of writings by Confucian scholars and other popular texts for which there was demand in the local area, before the publisher started to expand into woodblock prints and other artwork. Most notably, Tōshirō published a collection of “Hokusai manga”, a collection of sketches from the famous woodblock artist Katsushika Hokusai.

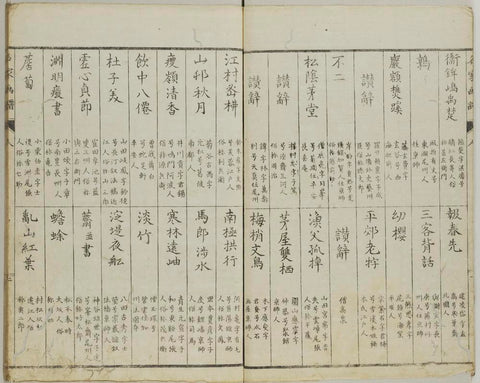

So what was the Meika Gafu? Literally translated, “A Book of Paintings by Celebrated Artists” was a selection of notable and praised artists’ work from the Bunka era and reproduced in a collection of three volumes, two of which survive to this day. The book was structured almost as an educational resource, with a table of contents organising the spreads of art according to artist, period and theme, like an encyclopaedia. Not only did they include the great classic painters in their omnibus, but also a selection of contemporary or lesser-known artists to educate and inform the whole country on the great wealth of art, both past and present, in their country. This wide-ranging collection appealed greatly to the Japanese public and was reprinted several times, giving the people a way to experience the art that was previously only accessible by the higher classes.

Accessibility was one of the most revolutionary things about the printing process in Japan. Woodblock printing was introduced as far back as the 2nd century BC, but was not popularised until the Edo period, which lasted from 1603 to 1868. The ability to mass produce copies of the most famous artwork in the country allowed everyone to own some artwork in their home, even when the ruling class didn’t allow them to hang larger pieces of art. This democratisation of art was incredibly important in the cultural awareness and literacy of the people of Japan, who were now able to experience everything from philosophical scriptures to contemporary masters such as Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige.

Matsumoto Hoji’s Frog was one of these pieces that made it’s way into the hands of the Japanese public, being published in volume 3 of the Meika Gafu. Beyond that, while we can see the frog as a motif in his other remaining artworks, we know nothing else concrete about the man. Was he a heralded great in his time? Or simply included as one of the lesser-known “up and comers” that publisher Tōshirō wanted to introduce to the public? We will probably never know. But what we do know is that this 200 year old frog is still capturing the hearts and imaginations of the public today, and probably will for several hundred years to come.

See more from Matsumoto Hoji here.

Comments (1)

Maria Beatriz Rico Pareja 11/07/25

I really aprecciated all rooms or galleries explores.